Architecture

Viaduct Architecture

This document provides a high-level description of Viaduct’s software architecture and how that relates to the organization of its source code. Viaduct consists of two main pieces, the runtime system and the build-time system. We look at each in turn.

Runtime Architecture

Software Layers

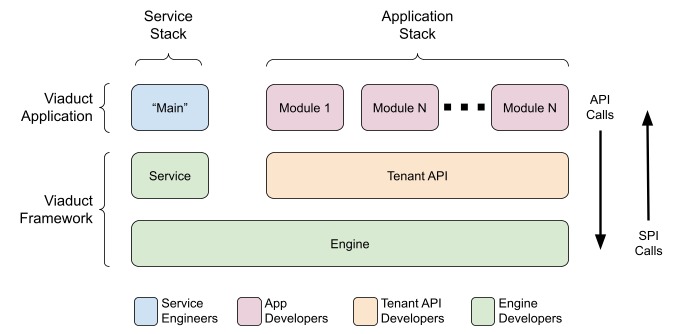

The following diagram illustrates the layers that make up the Viaduct architecture and the personas responsible for each layer:

Viaduct architecture layers and developer personas.

-

Overall a Viaduct application consists of two layers, the Viaduct Framework, i.e., the open-source software found in github.com/airbnb/viaduct, plus the application software that sits on top of that. In addition, it’s organized into two “stacks,” the service stack and the application stack.

-

The Viaduct Framework in turn consists of two internal layers: the engine and the tenant developer API. The engine implements the GraphQL execution algorithms. Internally this layer is written in a dynamically-typed manner: think of GraphQL objects represented as maps from field names to

Any?values (it’s more complicated than that, but directionally that’s the way to think about it). The tenant developer API provides an ergonomic layer for application developers sitting on top of this lower-level. Among other things, the tenant developer API presents statically-typed wrappers around the lower-level, dynamically-type engine objects, providing type safety for application code.- Viaduct was designed to support multiple different tenant developer APIs running at the same time. In fact, inside of Airbnb, we run two tenant developer APIs, one that implements our “Classic” tenant developer API supporting the 1.5M lines of existing code running in Viaduct today, as well as the new “Modern” tenant developer API which ships with the open-source code. In the future, we hope to implement a native Java API for writing Java-based application code, and even a JavaScript API. In our multi-tenant-API, these APIs would interoperate, e.g., a Viaduct installation could support application code written in both Kotlin and JavaScript.

-

Running on top of the Viaduct Framework is an installation’s application code.

-

Viaduct is also organized into two stacks:

-

The Service Stack contains the “Main” function that starts up a Viaduct application. Typically, this function creates a Web server that routes HTTP requests to the Viaduct engine. However, in some contexts the Main function might integrate the Viaduct engine into a test harness, or even a command-line tool. This Main function sits on top of a thin layer of software inside of Viaduct called the “service domain.” (We’ll say more about “domains” later.) The service domain consists mainly of factories and other abstractions that allow one to configure a Viaduct engine.

-

The Application Stack executes GraphQL operations, calling into application code as appropriate.

-

APIs and SPIs

The Viaduct architecture carefully distinguishes Service Provider Interfaces from Application Programming Interfaces. The arrows on the right side of the diagram indicate the difference between the two. SPIs call “up” through the software layers, enabling the Viaduct framework to call “into” application level code. APIs call “down” through the software layers, enabling Viaduct application code to invoke functionality provided by the framework. We’ll illustrate the difference shortly in the Sequence Diagram section. (Perhaps confusingly, we often use the term “API” imprecisely to refer collectively to both what we’re defining as the API and SPI here. TODO: Need some kind of qualifier for API we can use when we need to be more precise.)

Developer Personas

In our software architecture we identify four developer personas. Two of these – engine and tenant-API developers – work on their respective sublayers of the framework. (We consider the service domain to be an extension of the engine, and thus in the purview of engine developers.)

The other two personas work on applications running on top of the framework. Application developers are those who write the actual application, crafting the central schema and the business logic that make up a particular application. Service Engineers are those who integrate Viaduct into an organization’s IT stack. These include integrations into the organization’s preferred Web-serving framework, observability infrastructure, access-control platforms, and dependency-injection framework. These integrations are performed mostly by utilizing the SPIs mentioned earlier. Where multiple tenant-APIs are available, Service Engineers configure which ones are actually provisioned at runtime. Service Engineers are also responsible for organizing an application’s source code, setting up the build system and integrating it into the organization’s CI/CD infrastructure.

Request Sequence Diagram

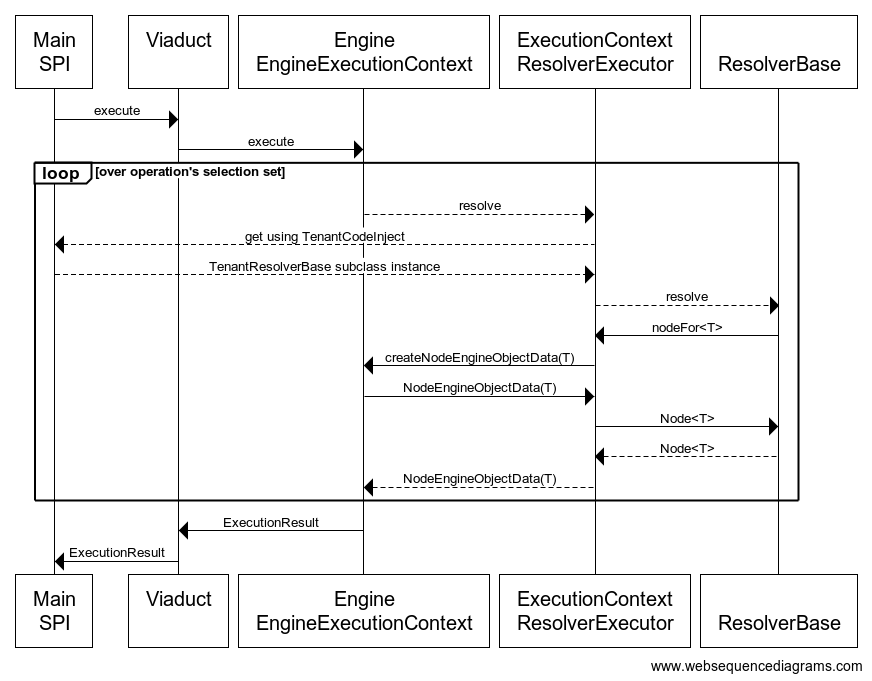

The following sequence diagram follows the lifecycle of an operation, highlighting the respective roles of the API and SPI:

A sequence diagram of the lifecycle of an operation.

The text in each of the “participant” boxes consists of two lines: the first line names the “API” abstractions, where the second line names the “SPI” abstractions (in every participant except for Main/SPI, the names given are the names of actual types in the Viaduct source code). In this diagram, solid-line arrows represent API calls as defined above, and dotted-lines represent SPI calls.

The Viaduct interface lives in the service domain and is the entry from the application’s “Main” function into the engine. As mentioned earlier, this is really a thin wrapper around an Engine object. So through Viaduct execution of an operation enters the Engine, which implements the GraphQL execution algorithm, invoking tenant module resolvers where appropriate. The sequence diagram illustrates how these invocations work. The Engine calls an SPI it defines called ResolverExecutor (there are two of these: NodeResolverExecutor and FieldResolverExecutor). The tenant-API implementation is responsible for providing instances of these resolver executors that perform the “wrapping” mentioned above – wrapping the dynamically-typed Engine abstractions with compile-time typed tenant developer API abstractions – and then calls an SPI that it (the tenant-API implementation) defines called ResolverBase.

To invoke the application-layer resolver code, the tenant-API implementation first needs to create an instance of the ResolverBase subclass containing the resolver function. This occurs by using an instance of TenantCodeInjector (an SPI) provisioned by Service Engineers when the configure Viaduct.

Once this chain of SPI enters into tenant module code, that tenant module code in turn uses the tenant developer API’s API abstractions – such as ExecutionContext – to leverage functionality provided to by the framework. In this particular example, the resolver is creating a “node reference” by calling ExecutionContext.nodeFor. Under the covers, the tenant-API’s implementation uses an EngineExecutionContext object – EngineExecutionContext.createNodeReference in particular – to create this node reference. In our hypothetical example, this node reference is what is then returned by the resolver function, and in turn the ResolverExecutor, back to the engine.

Source Code Structure

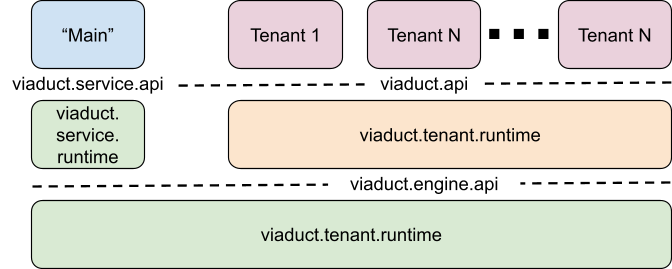

As implied above, the source code for the Viaduct Framework is divided into three Gradle projects: engine, service, and tenant. Each of these projects is organized into three Gradle subprojects: api, runtime, and wiring. The api subproject (which defines, e.g., the viaduct.engine.api package hierarchy) defines the API for the project (the engine API in this example). The SPI for the project is also in the api subproject (viaduct.engine.api.spi in the case of the engine). The api packages typically define Kotlin interfaces rather than classes. The runtime subproject (which defines, e.g., viaduct.engine.runtime) contains the implementation of that project’s API. This code structure relates to our architecture as follows:

A diagram of Viaduct’s source code structure.

(Note that, to reduce possible confusion by tenant developers, who use the tenant domain’s api package directly, types defined by the tenant api project are in the viaduct.api package hierarchy rather than in viaduct.tenant.api.)

As this diagram is meant to imply, consumers of a domain consume it through the types in its api project. They do not take direct dependencies on runtime projects. However, those consumers do need factories and other mechanisms to create instances of the api types. These are found in a domain’s wiring project. In Gradle, a domain’s wiring project takes an API dependency on the domain’s api project, and an implementation dependency on its runtime project. Consumers of the engine and service domains take an implementation dependency on their respective wiring projects - which will pull in their APIs as a compile-time dependency.

The tenant module domain is a little different. Tenant developers never instantiate tenant.api types directly, rather instances of those types get passed via SPIs. Thus, there is no wiring project for the tenant domain. However, that domain does have a bootstrap project, which is intended to be used by Service Engineers to bootstrap the tenant developer API. (This bootstrap project plays a similar role as the wiring project for the other domains, i.e., a mechanism to create instances. However, where wiring projects create instances of types in their respective api domains, the tenant bootstrap project creates instances of the engine’s SPI (in particular, TenantAPIBootstrapper). To avoid confusion, we’ve used a different name.)

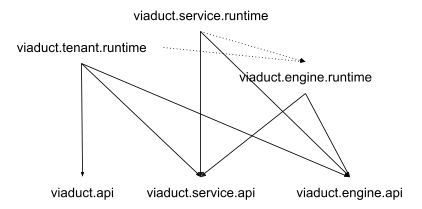

Detailed dependencies:

A diagram of dependencies between Viaduct’s source code modules.

The dotted lines represent an indirect dependency accomplished via the wiring project. The idea is that the three api projects are leaves in our dependency tree; the service and tenant domains access the engine implementation through its wiring project. The engine gets passed implementations of viaduct.service.api.spi interfaces via the viaduct.services.api.Viaduct builder, and it in turn passes those into the tenant runtime via the engine’s SPI classes. (This is where we want to be, it’s not where we are today - there are quite a few violations that we are working to clean up.)

Feedback

Was this page helpful?

Glad to hear it! Please tell us how we can improve.

Sorry to hear that. Please tell us how we can improve.